Fields

A field is a way of explaining action at a

distance. Massive particles

attract each other. How do they do this, if they are not in contact with

each other? We say that massive particles produce gravitational fields.

A field is a condition in space that can be probed. Massive

particle are also the probes that detect a gravitational field. A

gravitational field exerts a force on massive particles. The magnitude of the

gravitational field produced by a massive object at a point

P is the gravitational force per unit mass it exerts on another massive

object located at that point. The direction of the gravitational field is

the direction of that force

A field is a way of explaining action at a

distance. Massive particles

attract each other. How do they do this, if they are not in contact with

each other? We say that massive particles produce gravitational fields.

A field is a condition in space that can be probed. Massive

particle are also the probes that detect a gravitational field. A

gravitational field exerts a force on massive particles. The magnitude of the

gravitational field produced by a massive object at a point

P is the gravitational force per unit mass it exerts on another massive

object located at that point. The direction of the gravitational field is

the direction of that force

The magnitude of the gravitational force near the surface of Earth is F = mg,

the gravitational field has magnitude F/m = g. Its direction is downward.

Charged particles attract or repel each other, even when not in contact with

each other. We say that charged particles produce electric fields.

Charged particles are also the probes that detect an electric field. An

electric field exerts a force on charged particles. The magnitude of the

electric field E produced by a

charged particle at a point P is the electric force per unit positive charge

it

exerts on another charged particle located at that point. The direction of

the electric field is the direction of that force on a positive charge.

The actual force on a particle with charge q is given by F = qE.

It points in the opposite direction of the electric field E for a

negative charge.

In the presence of many other charges, a charge q is acted on by a net force

F,

which is the vector sum of the forces due to all the other charges.

The electric field due to all the other charges at the position of the charge q

is E = F/q, i.e. it is the vector sum of the electric fields

produce by all the other charges. To measure the electric field

E at a point P due

to a collection of charges, we can bring a small positive charge q to the point

P and measure the force on this test charge. The test charge must be

small, because it interacts with the other charges, and we want this interaction

to be small. We divide the force on the test charge by the magnitude of

the test charge to obtain the field.

Consider a

point charge Q located at the origin.

Consider a

point charge Q located at the origin.

The force on a test charge q at position r is

F = (keQq/r2)

(r/r).

The electric field produced by Q is

E = F/q

= (keQ/r2)

(r/r).

If Q is

positive, then the electric field points radially away from the charge.

The electric field decreases with

distance as 1/(distance)2.

If

Q is negative, then the electric field points radially towards the

charge.

If

Q is negative, then the electric field points radially towards the

charge.

The electric field decreases with distance as 1/(distance)2.

We obtain the electric field due to a collection of charges using the

principle of superposition.

E = E(Q1) + E(Q2) +

E(Q3)

+ ... .

Field lines

Field lines were introduced by Michael Faraday to help visualize the

direction and magnitude of the electric field. The direction of the field at any

point is given by the direction of a line tangent to the field line, while the magnitude of the

field is given qualitatively by the density of field lines. The field lines

converge at the position of a point charge. Near a point charge their density

becomes very large. The magnitude of the field and the density of the field

lines scale as the inverse of the distance squared.

Field lines

start on positive charges and end on negative charges.

Rules for drawing field lines:

- Electric field lines begin on positive charges and end on negative

charges, or at infinity.

- Lines are drawn symmetrically leaving or entering a charge.

- The number of lines entering or leaving a charge is proportional to the

magnitude of the charge.

- The density of lines at any point (the number of lines per unit length

perpendicular to the lines themselves) is proportional to the field

magnitude at that point.

- At large distances from a system of charges, the field lines are equally

spaced and radial as if they came from a single point charge equal in

magnitude to the net charge on the system (presuming there is a net charge).

- No two field lines can cross, since the field magnitude and direction

must be unique.

Examples:

Examples:

The field lines of an electric dipole,

i.e. a positive and a negative charge of equal magnitude, separated by a

distance d.

The electric field decreases

with distance as

1/(distance)3, much faster than the field of a point

charge.

The field lines of two positive charges of equal

magnitude separated by a

distance d.

The field lines of two positive charges of equal

magnitude separated by a

distance d.

The electric field decreases with distance as 1/(distance)2.

Polar molecules do not have a net charge, but the centers of the positive and

negative charge do not coincide. Such molecules produce a dipole field and

interact via the electrostatic force with their neighbors.

Example:

Every water molecule (H2O) consists

of one oxygen atom and

two hydrogen atoms. A water molecule has no net charge because the

number of positively charged protons equals the number of negatively

charged electrons in each atom. In the water molecule, each hydrogen

atom is bound to the oxygen atom by a covalent

bond. The hydrogen atom and the oxygen atom share an

electron, which has a slightly higher probability to be closer to the

oxygen atom than to the hydrogen atom. This results in a polar molecule, in which the

oxygen

"side" of the molecule has a slight negative charge, while the hydrogen

"sides" have a slight positive charge. Because water is a polar

molecule it dissolves many inorganic and organic materials. Organisms

can build macromolecules to attract or repel water as needed simply by

varying the charge on side chains.

Every water molecule (H2O) consists

of one oxygen atom and

two hydrogen atoms. A water molecule has no net charge because the

number of positively charged protons equals the number of negatively

charged electrons in each atom. In the water molecule, each hydrogen

atom is bound to the oxygen atom by a covalent

bond. The hydrogen atom and the oxygen atom share an

electron, which has a slightly higher probability to be closer to the

oxygen atom than to the hydrogen atom. This results in a polar molecule, in which the

oxygen

"side" of the molecule has a slight negative charge, while the hydrogen

"sides" have a slight positive charge. Because water is a polar

molecule it dissolves many inorganic and organic materials. Organisms

can build macromolecules to attract or repel water as needed simply by

varying the charge on side chains.

Problem:

Problem:

The figure on the right shows the electric field lines for a system of two point

charges.

(a) What are the relative magnitudes of the charges?

(b) What are the signs of the charges?

Solution:

- Reasoning:

Rules for drawing field lines:

Electric field lines begin on positive charges and end on negative

charges, or at infinity.

The number of lines entering or leaving a charge is proportional to the

magnitude of the charge.

- Details:

(a) There are 32 lines coming from the charge on the left, while there

are 8 converging on that on the right. Thus, the magnitude of the

charge on the left is 4 times

larger than the magnitude of the charge on the right.

(b) The charge on the left is positive, the charge on the right is negative.

Please watch

this

video clip that helps you "see" the electric field!

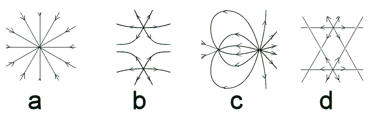

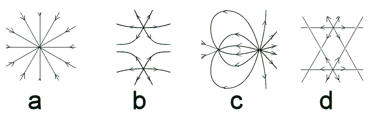

Embedded Question 2

Which of the diagrams below is not a valid field line diagram, and why?

Discuss this with your fellow students in the

discussion forum!

Review the rules for drawing electric field lines.

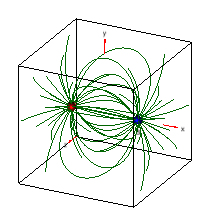

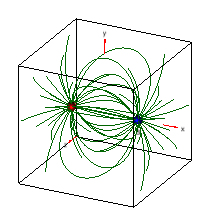

The electric field exists in 3-dimensional space. Below you can explore

3D drawings of the electric field lines of two charges.

Please click on the image!

You can change the

magnitude (arb. units), sign, and position (arb. units) of the each charge. You can use the mouse

to change your viewing angle and zoom in or out. To view field lines of

one charge only, choose zero for the magnitude of charge B.

Usually we try to visualize the magnitude and direction of the electric field

by drawing field lines in a plane in two dimensions. For two or three

charged spheres lying in a plane, we could draw the projections of the field

lines onto this plane. But that would make it impossible to represent the

exact direction of each line. We could also only draw field lines that lie

in that plane. Then the directions of the drawn lines would be correct,

but we would missing most of the lines, and the number of lines would not be

proportional to the magnitude of the charge. So we make a hybrid 2D

drawing. For the directions, we only choose field lines lying in the

plane, but we scale the number of these lines up to the number we would get from

a projection. Therefore, for charged spheres lying in a plane, the field

strength in a 2D drawing is not proportional to the density of the field lines,

but to the square of the density of the lines.

Forces and fields due to continuous charge distributions

Even though charge is quantized, we often can treat it as being continuously

distributed inside some volume, since one quantum of charge is a tiny amount of

charge. On a macroscopic scale we define the

volume charge density ρ = limΔV-->0(ΔQ/ΔV) as the charge per

unit volume, the surface charge density σ = limΔA-->0(ΔQ/ΔA) as the charge per

unit area, and the line charge density λ = limΔL-->0(ΔQ/ΔL) as the charge per

unit length.

We then have for the electric field of a distribution of charges

in a volume V

E(r) = [1/(4πε0)]∑iqi(r

- ri)/|r - ri|3] -->

[1/(4πε0)][∫v'

dV' ρ(r')(r - r')/|r

- r'|3.

Here

(r

- ri)/|r - ri| is the unit vector pointing from

ri

to r, and

(r - r')/|r

- r'| is a unit vector pointing from

the volume element dV' at r' to r.

If the charge is distributed over a surface, then ρdV --> σdA, where σ is the surface

charge

density and dA is an element of surface area. For a line charge distribution we have

ρdV --> λdl, where λ

is the line charge density and dl is an element length.

Problem:

Consider a line charge with line charge density λ = Q/2a that extends along

the x-axis from x = -a to x = +a. Find the electric field on the y-axis.

Solution:

- Reasoning

We are asked to find the electric field due to a line charge distribution.

This is a continuous charge distribution.

We find the he field on the y-axis due to an infinitesimal element of charge λdx

at position x and the integrate over all positions x from x = -a to x = +a.

- Details of the calculation:

The field on the y-axis due to an infinitesimal element of charge λdx is given

by

dEx = (keλdx/(x2 + y2)) cosθ,

dEy

= (keλdx/(x2 + y2)) sinθ,

where cosθ = x/(x2 + y2)½, sinθ = y/(x2

+ y2)½.

On the y-axis the field due to the line charge therefore is given by

Ex = keλ∫-aaxdx/(x2 +

y2)3/2

= 0 from symmetry, and

Ey = keλy∫-aadx/(x2 +

y2)3/2.

Using ∫-aadx/(x2 + y2)3/2

= 2a/(y2(a2 + y2)½)

we have Ey = keλ 2a/(y(a2 +

y2)½)

= keQ/(y(a2 + y2)½)

The electric field on the y-axis points in the positive y-direction for y > 0

and in the negative y-direction for y < 0.

As y becomes very large, we can neglect a2

compared to y2

under the square root and then Ey = keQ/y2 ∝

1/y2. From very far away, the line charge looks like a point charge.

If, on the other hand, the line is very long, and we y << a, then we can neglect

y2 compared to a2 under the square root and then Ey

= keQ/(ay) ∝ 1/y. Near a very long line charge the electric

field falls off as 1/distance, not as 1/distance2.

Simulation:

Electric Field

Hockey

- This simulation looks down on an air hockey table. Instead of

hitting the puck, you move it using charges.

- Use the Practice mode for testing your ideas.

- Clear zeros everything, and Reset brings the puck back to the starting

point with the same charges.

- You can change the sign of the charge on the puck by checking or

un-checking the Puck is Positive option.

- You may want to investigate how to use multiple charges to make a goal.

External link to other web material:

The Physics Classroom:

Static Electricity

A field is a way of explaining action at a

distance. Massive particles

attract each other. How do they do this, if they are not in contact with

each other? We say that massive particles produce gravitational fields.

A field is a condition in space that can be probed. Massive

particle are also the probes that detect a gravitational field. A

gravitational field exerts a force on massive particles. The magnitude of the

gravitational field produced by a massive object at a point

P is the gravitational force per unit mass it exerts on another massive

object located at that point. The direction of the gravitational field is

the direction of that force

A field is a way of explaining action at a

distance. Massive particles

attract each other. How do they do this, if they are not in contact with

each other? We say that massive particles produce gravitational fields.

A field is a condition in space that can be probed. Massive

particle are also the probes that detect a gravitational field. A

gravitational field exerts a force on massive particles. The magnitude of the

gravitational field produced by a massive object at a point

P is the gravitational force per unit mass it exerts on another massive

object located at that point. The direction of the gravitational field is

the direction of that force Consider a

point charge Q located at the origin.

Consider a

point charge Q located at the origin. If

Q is negative, then the electric field points radially towards the

charge.

If

Q is negative, then the electric field points radially towards the

charge. Examples:

Examples: The field lines of two positive charges of equal

magnitude separated by a

distance d.

The field lines of two positive charges of equal

magnitude separated by a

distance d. Every water molecule (H2O) consists

of one oxygen atom and

two hydrogen atoms. A water molecule has no net charge because the

number of positively charged protons equals the number of negatively

charged electrons in each atom. In the water molecule, each hydrogen

atom is bound to the oxygen atom by a covalent

bond. The hydrogen atom and the oxygen atom share an

electron, which has a slightly higher probability to be closer to the

oxygen atom than to the hydrogen atom. This results in a polar molecule, in which the

oxygen

"side" of the molecule has a slight negative charge, while the hydrogen

"sides" have a slight positive charge. Because water is a polar

molecule it dissolves many inorganic and organic materials. Organisms

can build macromolecules to attract or repel water as needed simply by

varying the charge on side chains.

Every water molecule (H2O) consists

of one oxygen atom and

two hydrogen atoms. A water molecule has no net charge because the

number of positively charged protons equals the number of negatively

charged electrons in each atom. In the water molecule, each hydrogen

atom is bound to the oxygen atom by a covalent

bond. The hydrogen atom and the oxygen atom share an

electron, which has a slightly higher probability to be closer to the

oxygen atom than to the hydrogen atom. This results in a polar molecule, in which the

oxygen

"side" of the molecule has a slight negative charge, while the hydrogen

"sides" have a slight positive charge. Because water is a polar

molecule it dissolves many inorganic and organic materials. Organisms

can build macromolecules to attract or repel water as needed simply by

varying the charge on side chains.  Problem:

Problem: